The information within this article is now out of date but provides information that was correct at the time of publication. Please read our latest community news update: ProQR agreement with Laboratoires Théa for sepofarsen and ultevursen inherited retinal disease programs.

Patricia Biasutto, (former) head of sepofarsen for Leber congenital amaurosis “Top-notch science that leads to a treatment”

2017 may become a very exciting year for Patricia Biasutto, sepofarsen captain. The work of her department, aimed at developing a novel drug for Leber congenital amaurosis 10 (LCA10) patients, has progressed steadily. The team is expecting to start a first clinical trial in patients this year.

Patricia Biasutto, born and raised in Venezuela and now heading ProQR’s LCA research and development team in Leiden (The Netherlands), has multiple reasons for being optimistic. Obviously, as a biotech scientist looking for a treatment for LCA, she cannot confirm that there is a breakthrough. Not yet. “We have definitely found something. ProQR’s team has developed a molecule that shows promising results in laboratory tests. In collaboration with various academic centers we have made tremendous progress and in 2017 we will take development to the next phase: clinical trials.”

Change the lives of patients

In search for the one molecule that may change the lives of the 2,000 patients (see text box) that suffer from LCA10, Biasutto and her colleagues applied what she describes as “the amazing innovative retinal organoid model of ‘optic cups’.” She explains, in a short lecture: “Before we can test our molecule in patients we first need to find out whether it works.

For LCA10 we had no good models to test this in and you cannot just take an eye from a patient! We worked together with the University College London (UCL) that recently developed this amazing technique where you can take a bit of skin from an LCA10 patient and turn the cells into stem cells and basically grow retinas in the laboratory. We were one of the first companies to use this 3D organoid model and with it show that sepofarsen does exactly what we hoped it does in the closest representation of a patient’s retina.”

The key to patient benefit

In the laboratory, the team found confirmation that the sepofarsen molecule restores the RNA sequence of the CEP290 protein that has a very important role in keeping photo-receptor cells (rods and cones) alive in the retina. In LCA10 patients, this protein is not formed. Hence, the photo-receptor cells in the retina die and – with that – the ability to see. “Restoring production of this protein may be the key to keep the retinas intact and prevent blindness. The next, exciting step will be clinical testing in patients.” Until now, every one of these steps, every new test produces another ‘green light’. “Seeing the molecule perform well in the ‘optic cup’ model is truly exciting. It is the sensation that scientists, like me, flourish on”.

Patricia calls the process of becoming aware of the molecule’s potential “a very fulfilling experience” and “an amazing feeling”. “But as much as I celebrate it, the life-changing moment has yet to come. That will have to come when the molecule actually proves to be effective in a patient. We took the first step – or hurdle. There is a green light, but we need more of them.”

“It is all about people”

ProQR may not be the largest biotech company in the world today, not by far. To Patricia, the size is irrelevant, as even the smallest of biotech firms can achieve great results. “It is all about people, their knowledge and their experience. It is about putting the right teams together, to find the right entrepreneurial and scientific chemistry”. Patricia insists that innovation can only be born in environments without boundaries, where scientists feel they can unleash their creativity. “It can only happen when you feel free to challenge your co-workers in a professional way and when you know your efforts are valued. I think ProQR does perform exceptionally well in this area – it is a particularly nourishing environment, especially when you need to work long hours and weekends to find solutions to tough problems.”

Creativity and perseverance

To Patricia Biasutto, success in biotech research comes from mixing creativity and perseverance – and a little bit of luck. “You need to have a vision of what you want to achieve, as you need some sense of direction. You need to be curious to find new ways of applying RNA technologies – tested or not – to genetic diseases. You need strong partnerships with the best academic centers, their research and their tools. I guess that when a company has all that – and this applies to ProQR – there is a great chance of success.”

Next steps

What are the next steps to bring sepofarsen to patients? “In our upcoming trial we aim to make sure our molecule is safe, but the trial will also tell us much about the efficacy.” Patricia stresses the importance of involving patients, as of part ProQR’s patient-centric approach. “We want sepofarsen to be administered in the most comfortable and effective way. To ensure this we are always looking to communicate with patient groups to tap into their expertise. There is also a practical aspect in designing a trial and providing information that is accessible for people who are visually impaired.”

For LCA10 patients, 2017 could be a year of promise. “And of hope”, Patricia adds. What is the ultimate dream? “Repairing sight for all patients with inherited blindness. Or at least to stop the progression of these diseases in young patients.”

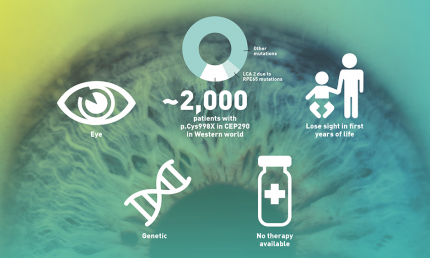

LCA10 basics

A clinical trial SAVED MY LIFE. That event strengthens my personal motivation.

A personal angle

In Patricia Biasutto’s mind, there is no doubt that the molecule will reach the all-important phase of clinical trials. Her optimism is purely scientifically-based, but there is also a more personal angle to this. “In short, a clinical trial saved my life. That life event strengthens my personal motivation to get QR‑110 to the clinical trial phase ASAP.” She explains: “When I was a child, I suffered from cancer. It was a severe, life-threatening type of cancer. My future was very uncertain, the doctors had very limited options to treat the cancer which unfortunately did not work to stop the disease. At that time, a new combination of drugs just reached the clinical trial phase. My very caring and committed doctors with my parent’s support managed to get me on the program. That is the reason why I am here today.”

A scientific connection

It was this event that eventually brought Patricia to ProQR. When ProQR was founded, Patricia was among the first to join. “There were only five people working here. At the time, I was working in Paris. Taking the job interview by Skype did not feel right, so I volunteered to pay for my round-trip to come over to Leiden to have it in person. Looking back at it, it was the right decision. It was like love at first sight with the team. There was this immediate connection with the founder and CEO, Daniel de Boer, who’s initial motivation to start this business was to find a cure for his son’s disease, CF. In my four years at ProQR, I never once doubted my decision.”

What defines this connection, this common goal? “It is the shared awareness that, in this profession and at this company, we truly have the potential to change patients’ lives. This is not just a job. I am thrilled that soon, we may be able to offer patients the opportunity that saved and shaped me. To anyone else, clinical testing is just a technical term. To me, it is much more than that. It is hope.”

Optic cup

There are over 300 genetic diseases that can cause blindness and we have chosen to make these important targets for our quest for treatments. Our lead program is for Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA), a rare genetic eye disease characterized by progressive loss of vision. Depending on the genetic mutation patients usually become completely blind during the time between birth and the age of 8. As such, LCA is the leading cause of genetic blindness in children. We also develop programs for other inherited blindness called Usher syndrome and Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy.

The key player in LCA10 – the most severe form of LCA, affecting approximately 2,000 patients in the Western world – is the CEP290 protein. This protein helps the development of cilia in the photo receptor cells (rods and cones) in the retina. A non-functioning CEP290 protein causes subsequent retinal degeneration in LCA10 patients.

In a healthy eye, the outer segment of light detecting cells (rods and cones) in the retina are constantly renewed, a process in which the CEP290 protein plays a major part. It facilitates the transport of new ‘building materials’ to the outer segments to keep them alive. Due to a defect in the DNA of LCA10 patients, this crucial protein is not produced. As a result, the light detecting cells are not maintained and the cells die, leading to poor vision and – eventually – blindness.

ProQR is developing a novel RNA therapy for LCA10 patients, called sepofarsen. The molecule is specifically designed to exclude the p.Cys998X mutation that is present in the CEP290 mRNA of some LCA10 patients. This mRNA is the ‘blueprint’ of the CEP290 protein. By fixing this blueprint a normal healthy CEP290 protein will be formed that is expected to have normal function. The goal of sepofarsen is to stop the progression of or potentially even reverse some of the effects of LCA10 caused by the p.Cys998X mutation.

Source: ProQR’s Annual Magazine 2016

Learn more about sepofarsen for CEP290 LCA.